Amparo Alonso holds a PhD in Specific Didactics in Visual Arts from the University of Valencia. Her research focuses on Children’s Visual Culture, Teacher Training, Art Education, and the Aesthetic Quality of Educational Centers, linked to well-being in the classroom.

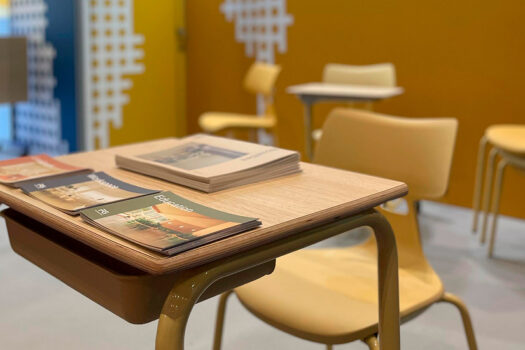

1. The arrangement of furniture and classroom layout are key areas of research. In what way does the traditional model—rows of chairs facing the teacher—shape the teaching and learning experience? What kind of educational model does it promote?

Amparo Alonso: The professional’s profile and documentary style are reflected in the pedagogical models they employ, as well as in the spatial arrangements they use, which align with what makes them feel comfortable. Conversely, a traditional arrangement of chairs in rows facing the teacher influences the types of activities that take place, shaping not only the teacher’s approach but also the students’ attitudes, predisposing them to a specific mode of learning.

The teaching model conveyed by the row-based classroom arrangement prioritizes procedural production, individual or serialized work, and the centralization of tasks on a surface that fits on a desk (such as sheets of paper or notebooks). It discourages dialogue or collaboration with nearby peers and fosters a receptive approach to knowledge.

Above all, it reinforces the idea that knowledge resides in the teacher, who stands in front of a group of student-spectators arranged behind them. This setup establishes a hierarchical, top-down relationship and directs the learner’s gaze toward a single classroom wall—typically where the blackboard is located—focusing all attention there.

However, there are no inherently anti-pedagogical desks or chairs, nor are there layouts that should be banned. The row-based arrangement can be very useful for activities that require mirroring, where students need to imitate someone positioned in front of them.

What matters is taking responsibility for choosing the most suitable arrangement for each learning objective and being proactive in adjusting it as needed—whether within a single session, throughout the day, over a month, or across the semester.

2.- It is common for the teacher to change positions in the classroom, and students may also move with the teacher’s permission. But what pedagogical and social opportunities arise when it is the materials—or even the furniture—that change location?

Amparo Alonso: The distribution of resources on a global scale is neither equitable nor even proportional. However, in schools—seen as democratizing environments—we tend to distribute materials and furniture equally. We usually have the same number of chairs and desks as students, as many scissors, boxes of crayons, or books as there are people. I think about the social possibilities in schools, where there is an opportunity to raise awareness of inequalities, starting with the distribution of resources.

Let’s imagine, for example, a situation where some work materials are only available on certain desks, others on different desks, while some groups don’t have any resources at all. We would encounter the same conflicts students might face outside the classroom. From these conflicts, we could foster reflection, empathy, generosity, but also competition, effort, and achievement. Students would develop social skills to tackle the challenges we set for them. Schools must prepare us for contemporary realities.

Or imagine placing the materials in the center of the classroom, with students using them gathered around. The flow of students should be constant, allowing them to observe their peers’ work and interact face-to-face around the resources. This arrangement encourages collaboration, observation, and a shared engagement with the learning materials.

The pedagogical possibilities of modifying the furniture layout are vast. They can all facilitate dialogue, whether by pairing or grouping students. But there are also more extreme examples that can be useful at times: promoting movement and encouraging students to adopt different postures when sitting, which may be uncomfortable; sparking creativity, wonder, and motivation by breaking any routine (such as having students work on a desk with the legs facing upward); or shifting the balance toward the students and restoring the teacher’s prominence by removing their desk, among others.

3.- How do you think the environment—its aesthetics, even—affects students’ attention in the classroom?

Amparo Alonso: The environment can influence students positively or negatively, but it is never neutral. Similarly, there is no single environment that suits all student profiles. Some need a space for calm, relaxation, and tranquility, while others require an area for free movement within the same space. It is true, however, that there are shared aesthetic preferences among young people: welcoming, warm, and homely spaces; places with which they establish a sense of belonging; versatile places.

Personally, I am not as concerned with the student’s attention in class as I am with their well-being. I believe that a child who feels comfortable in their learning environment, even if they don’t learn exactly what the teacher intends, is likely to learn something different that does capture their attention. In this sense, aesthetics play a significant role in contributing to the quality of education, particularly when it comes to comfort and well-being.

4.- From your research with young children, it appears that common learning areas and tasks that are freer or more artistic are the ones children prefer. How can I help improve interpersonal relationships among students?

Amparo Alonso: By blurring the boundaries of the furniture, interpersonal relationships can be improved. The furniture should not be an obstacle but rather a facilitator. It should not act as a barrier or a border, but as a mediating vehicle.

We must stop thinking of school furniture as just a chair and a desk, and start visualizing it more as a surface. School furniture should be considered as support for the body in all its dimensions and postures, as well as support for the tools and materials used in work.

School furniture can contribute to improving interpersonal relationships by extending from the floor to the walls, windows, and ceiling. If the furniture blends with other areas, learning can take place in different corners, in various positions, with new rules of engagement.

5.- In the classes taught at the University of Valencia, is there room to modify the classroom structure to achieve greater student motivation?

Amparo Alonso: And if there is no room for change, we try to break free from the constraints. For example, we’ve revived the practice of hanging student work on the walls, and when we faced resistance to damaging the vertical surfaces, we creatively turned to drawing, painting, and collaging on the glass of the large windows, which doesn’t get damaged and is easy to clean.

We have emphasized that changing the structure of the classroom means, at first, stepping outside of the classroom itself. Guided by this instinct, we have taught and learned in the elevators, bathrooms, hallways, and lobbies of the Faculty of Education, with artistic interventions that are both socially relevant and meant to be shared with the rest of the educational community.

And during a two-hour session, we find ourselves compelled to move from horseshoe arrangements to small circles, to a large circle of tables around the perimeter, or to an open classroom layout.

The margin for changing the attitude of the teacher and their enthusiastic students is limited because the furniture doesn’t move at the push of a button, nor is it lightweight or on wheels. To alter the structures, it requires the human energy of those who inhabit the classrooms.

6.- What requirements should current classroom furniture meet, at a time when teaching methodologies are changing?

Amparo Alonso: Some properties have always been essential, such as being economically affordable, durable, resistant, with rounded edges, and ergonomic.

But there are also other key aspects:

– It should be personalized for its users, at least allowing partial transformation. This could be as simple as being able to place a charm, a plant, or interchangeable images, change the color, or choose it.

– It should be versatile, lightweight, and silent when moved.

– It should not be viewed merely as a desk or chair, but as a surface for the body and a learning resource.

– It should facilitate relationships, not obstruct them.

7.- What is the main problem with education in Spain?

Amparo Alonso: The main issue is that education is not considered a matter of interest, but rather just a tool.